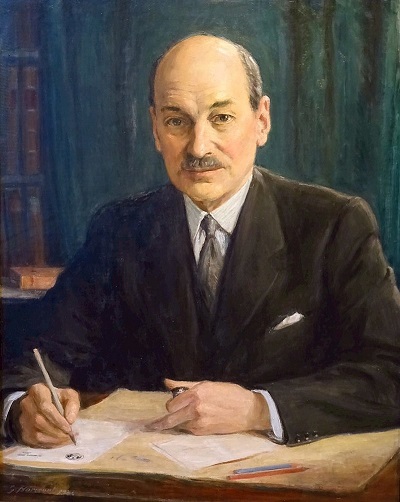

A pioneer of the Labour Party and Britain’s first post-war Prime Minister stood down as leader of his party on December 7th, 1955.

Clement Attlee was a surprise winner of the 1945 General Election, taking the Labour Party into power on the promise of widespread social reform and replacing Britain’s wartime leader Winston Churchill at 10 Downing Street.

It was the pinnacle of a long and distinguished political career for the solicitor’s son from Putney, who graduated from Oxford and qualified as a barrister before going into politics. But 63 years ago today, he stepped down as leader of what was by then the Opposition, following months of speculation.

It was the pinnacle of a long and distinguished political career for the solicitor’s son from Putney, who graduated from Oxford and qualified as a barrister before going into politics. But 63 years ago today, he stepped down as leader of what was by then the Opposition, following months of speculation.

Within hours of his resignation it was announced that the Queen would make him an earl, which would allow him to continue his work for the Labour Party in the House of Lords, where it had scant representation. He was the first Labour leader to accept a hereditary peerage.

Mr Attlee struggled to retain the support of his party after losing the 1951 General Election, which saw the Conservatives returned to power. He remained as leader of the Labour Party in opposition, but was dogged by constant rumours of his impending resignation or challenges to his leadership.

Failing health stoked the speculation after the 72-year-old Mr Attlee suffered a stroke in late 1955. He had served as an MP in the House of Commons for 33 years and led his party for 20 of those. In 1942 he became Deputy Prime Minister in the wartime coalition government under Winston Churchill and quickly proved himself a capable and effective leader. His personal popularity played a significant part in Labour’s General Election win at the end of the war in 1945.

Labour won again in 1950, but with a massively reduced majority, cut to just five seats. Post-war austerity was biting hard and many voters saw salvation in a change of government. The near-defeat caused growing rifts in the Labour Party which Attlee struggled to hold together. By spring of the following year he saw his only hope as a snap General Election – a gamble which he hoped would bring Labour a bigger majority in the Commons and reinforce his personal authority. But it was a gamble that failed, resulting in a narrow win for the Conservatives.

During his six years as Prime Minister, Attlee oversaw sweeping changes to British society, including the introduction of the NHS, major additions to the welfare state and the nationalisation of key industries including coal, telecommunications, transport, electricity, civil aviation and even the Bank of England. He also pushed through the independence of India and Burma

If anything, he was the victim of Labour’s success in these areas. So much change in such a short space of time could not be wrought without economic disruption and the Conservatives’ 1951 election win came on the promise of a return to stability and increased prosperity – a promise they struggled to keep.

Attlee’s government faced one of the biggest challenges in Britain’s political history – rebuilding an economy devastated by six years of total war, managing foreign policy in a highly unstable Europe (with the emergence of Soviet Russia as a world superpower), and fundamentally restructuring British society to better serve the majority of its people. It was a huge task, but one which was largely achieved under Clement Attlee’s stewardship.

He remained active in the House of Lords, playing a key part in decriminalising homosexuality and twice speaking against the UK’s application to join the Common Market, warning it would erode parliamentary democracy and restrict Britain’s worldwide trade.

Attlee lived long enough to see Labour return to power under Harold Wilson in 1964. He died peacefully in his sleep from pneumonia in October 1967 at the age of 84. Only after his death was his legacy to British politics fully recognised. His ashes are buried at Westminster Abbey.