Children all over Britain were celebrating on Thursday February 5th, 1953, for that was the day that sweets finally came off the ration!

Those who hadn’t yet started secondary school had never known a time when they (or their parents) could walk into the local sweet shop and buy whatever they liked, in whatever quantity they liked, without handing over the required coupons from the ration book.

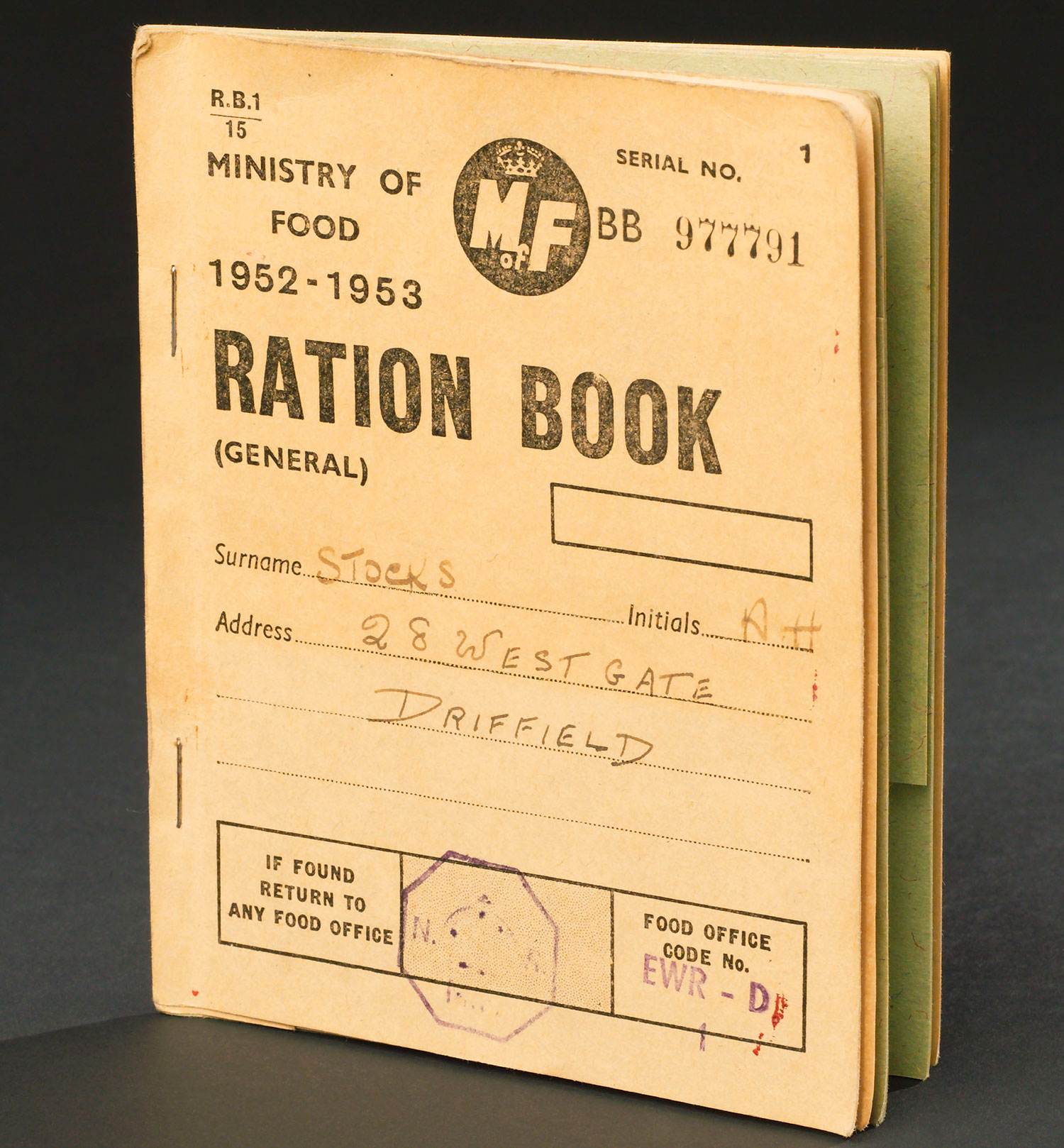

Rationing came into force in January 1940, just a few months into the Second World War, and covered all sorts of food items, as well as petrol, clothing and furniture. Sweets – seen as occasional treats – weren’t initially covered by rationing, but they were included from mid-1942 onwards.

Rationing came into force in January 1940, just a few months into the Second World War, and covered all sorts of food items, as well as petrol, clothing and furniture. Sweets – seen as occasional treats – weren’t initially covered by rationing, but they were included from mid-1942 onwards.

The war effort exhausted Britain’s resources and its funds to import goods from elsewhere, so rationing went on long after hostilities ended, and in some cases became stricter than during the war years! The process of taking items ‘off the ration’ began in 1948, with bread the first item to be ‘de-rationed’. Clothing came off the ration in 1949 and petrol in May the following year, but five years after the war’s end, people were increasingly impatient with the slow progress.

When a new Conservative government came to power in late 1951 it pledged to speed up the process. Meat and a few remaining foodstuffs were the last off the ration in July 1954.

The end of sweet rationing, on February 5th 1953, saw youngsters breaking open their piggy banks and heading for the sweet shop. They weren’t alone either, as many adults craved a sweet treat after the austerity of the war years and beyond. While rationing was in force, people could only buy a maximum 3oz of sweets per week, but in reality other more essential food items usually took priority in the family budget. Some people even considered it ‘unpatriotic’ to eat sweets, calling production of such ‘luxury items’ a waste of scarce resources.

There had been a previous attempt to de-ration sweets in April 1949, but demand immediately outstripped supply and they were quickly put back on the ration. This time the government had learned its lesson, ordering a one-off bulk allocation of sugar to help manufacturers meet the expected surge in demand. Consequently, shops were well-stocked ready for the rush.

Best sellers on the first day of de-rationed sweet sales were toffee apples, with bars of nougat, boiled sweets, chocolate and liquorice strips also selling fast. One London manufacturer gave 150lb of lollipops away free to 800 local children during their school lunch break, while another factory opened its doors to hand out free sweets to all comers. Manufacturers were also able to start packaging their goods in larger sizes again, with 2lb boxes of chocolates flying off the shelves.

There was some concern that if high demand continued beyond the expected initial surge, manufacturers would struggle to meet it, since sugar was still rationed. In the end it didn’t happen, partly because the cost of confectionery had risen sharply during the war years. Another reason was that many people, deprived of sweets for so long, had simply lost their ‘sweet tooth’, while most wartime children had never had the opportunity to acquire one.

In any case, sugar came off the ration eight months later, in September 1953. Eggs, cream, butter, margarine, cheese and cooking fats were also taken off the ration books by the Minister of Food, Gwilym Lloyd-George, who made de-rationing the number one priority for his department.

Demand for sweets and confectionary did start to rise again, but it was gradual process. In the first year after derationing, spending on confectionary in the UK rose to £250m, up by £100m from when rationing was in force. While that was a significant rise, much of it was accounted for by the initial surge in demand. Sweet sales didn’t start to rise steeply until the more affluent 1960s and ’70s, with new technology helping manufacturers develop an ever greater array of treats to tempt us.

Brits collectively now spend around £12 billion per year on sweets and confectionary. Health experts say this is a major factor leading to widespread obesity and tooth decay – problems which most 1940s children never had to worry about.